The Civil Rights Movement in the United States has been a long, primarily nonviolent struggle to bring full civil rights and equality under the law to all Americans. It has been made up of many movements, though it is often used to refer to the struggles between 1945 and 1970 to end discrimination against African Americans and to end racial segregation, especially in the U.S. South. The civil rights movement has had a tremendous and lasting impact on United States society, both in its tactics and in increased social and legal acceptance of civil rights.

Throughout the history of the United States, African Americans have resisted, first the institution of slavery and later second-class citizenship and racial segregation. Opposition took many forms, from the passive resistance of slaves who performed poor work for their masters, to slave revolts, to slaves escaping to freedom on the Underground Railroad, to African Americans' participation in the Abolitionist movement and fighting against the pro-slavery Confederacy in the American Civil War. Throughout the history of the United States, African Americans have resisted, first the institution of slavery and later second-class citizenship and racial segregation. Opposition took many forms, from the passive resistance of slaves who performed poor work for their masters, to slave revolts, to slaves escaping to freedom on the Underground Railroad, to African Americans' participation in the Abolitionist movement and fighting against the pro-slavery Confederacy in the American Civil War.

From the end of the Civil War to the 1960s, African Americans, especially in the south, faced constant prejudice. In many cities and towns, African Americans were not allowed to share a taxi with whites or enter a building through the same entrance. They had to drink from separate water fountains, use separate restrooms, attend separate schools, and even swear on separate Bibles and be buried in separate cemeteries. They were excluded from restaurants and public libraries. Many parks barred them with signs that read "Negroes and dogs not allowed." One municipal zoo went so far as to list separate visiting hours. From the end of the Civil War to the 1960s, African Americans, especially in the south, faced constant prejudice. In many cities and towns, African Americans were not allowed to share a taxi with whites or enter a building through the same entrance. They had to drink from separate water fountains, use separate restrooms, attend separate schools, and even swear on separate Bibles and be buried in separate cemeteries. They were excluded from restaurants and public libraries. Many parks barred them with signs that read "Negroes and dogs not allowed." One municipal zoo went so far as to list separate visiting hours.

Voting rights discrimination was widespread. Black voters faced severe persecution. Some were evicted from their homes, others had their names published in newspapers and had their character questioned. Many had to pass literacy tests not applied to their white counterparts. Some counties in the Deep South resorted to harsher means of preventing local blacks from voting. They jailed black applicants and firebombed places where voter education classes had been conducted. They threatened, beat, and in some cases, murdered black applicants. The Ku Klux Klan exerted an often-unchecked reign of terror across the South, where lynching of African Americans was a common occurrence and rarely prosecuted. Nearly 4,500 African Americans were lynched in the United States between 1882 and the early 1950s. Voting rights discrimination was widespread. Black voters faced severe persecution. Some were evicted from their homes, others had their names published in newspapers and had their character questioned. Many had to pass literacy tests not applied to their white counterparts. Some counties in the Deep South resorted to harsher means of preventing local blacks from voting. They jailed black applicants and firebombed places where voter education classes had been conducted. They threatened, beat, and in some cases, murdered black applicants. The Ku Klux Klan exerted an often-unchecked reign of terror across the South, where lynching of African Americans was a common occurrence and rarely prosecuted. Nearly 4,500 African Americans were lynched in the United States between 1882 and the early 1950s.

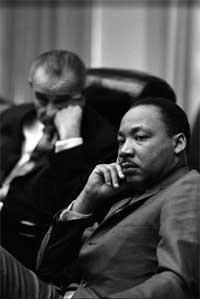

The leadership role of black churches in the movement was a natural extension of their structure and function. They offered members an opportunity to exercise roles denied them in society. Throughout history, the black church served not only as a place of worship but also as a community "bulletin board," a credit union, a "people's court" to solve disputes, a support group, and a center of political activism. These and other functions enhanced the importance of the minister. The most prominent clergyman in the civil rights movement was Martin Luther King, Jr. Time Magazine's 1964 "Man of the Year" was a man of the people. He joined as well as led protest demonstrations. King's powerful oratory and persistent call for racial justice inspired sharecroppers and intellectuals alike. His tireless personal commitment to and strong leadership role in the black freedom struggle won him worldwide acclaim and the Nobel Peace Prize. The leadership role of black churches in the movement was a natural extension of their structure and function. They offered members an opportunity to exercise roles denied them in society. Throughout history, the black church served not only as a place of worship but also as a community "bulletin board," a credit union, a "people's court" to solve disputes, a support group, and a center of political activism. These and other functions enhanced the importance of the minister. The most prominent clergyman in the civil rights movement was Martin Luther King, Jr. Time Magazine's 1964 "Man of the Year" was a man of the people. He joined as well as led protest demonstrations. King's powerful oratory and persistent call for racial justice inspired sharecroppers and intellectuals alike. His tireless personal commitment to and strong leadership role in the black freedom struggle won him worldwide acclaim and the Nobel Peace Prize.

Other notable minister-activists included Ralph Abernathy, King's closest associate; Bernard Lee, veteran demonstrator and frequent travel companion of King; Fred Shuttlesworth, who defied Bull Connor and who created a safe path for a colleague through a white mob in Montgomery by commanding "Out of the way!"; and C.T. Vivian,who debated Sheriff Clark on his conduct and the Constitution.

Students and seminarians in both the South and the North played key roles in every phase of the civil rights movement--from bus boycotts to sit-ins to freedom rides to social movements. The student initiated group The Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee or SNCC (pronounced "snick") was a powerful force in the movement. The student movement involved such celebrated figures as John Lewis, James Lawson, Bob Moses, James Bevel, and Stokely Carmichael. Students and seminarians in both the South and the North played key roles in every phase of the civil rights movement--from bus boycotts to sit-ins to freedom rides to social movements. The student initiated group The Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee or SNCC (pronounced "snick") was a powerful force in the movement. The student movement involved such celebrated figures as John Lewis, James Lawson, Bob Moses, James Bevel, and Stokely Carmichael.

In the early days of the civil rights movement, litigation and lobbying were the focus of desegregation efforts. The U.S. Supreme Court decisions in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka and others led to a shift in tactics, and from 1955 to 1965, "direct action" was the strategy--primarily bus boycotts, sit-ins, freedom rides, and social movements.

Churches and local grassroots organizations stepped in, and brought with them a much more energetic and broad-based style than the more legalistic approach of groups such as the NAACP. Locally initiated boycotts of segregated buses, especially the Montgomery bus boycott of 1955-1956, united and mobilized black communities on commonly-shared concerns. Protestors refused to ride on the buses, opting instead to walk or carpool. The nearly one year-long boycott ended bus segregation in Montgomery and triggered other bus boycotts such as the highly successful Tallahassee, Florida boycott of 1956-1957. Churches and local grassroots organizations stepped in, and brought with them a much more energetic and broad-based style than the more legalistic approach of groups such as the NAACP. Locally initiated boycotts of segregated buses, especially the Montgomery bus boycott of 1955-1956, united and mobilized black communities on commonly-shared concerns. Protestors refused to ride on the buses, opting instead to walk or carpool. The nearly one year-long boycott ended bus segregation in Montgomery and triggered other bus boycotts such as the highly successful Tallahassee, Florida boycott of 1956-1957.

In 1957, Septima Clarke, Bernice Robinson, and Esau Jenkins, with the help of the Highlander Folk School began the first Citizenship Schools in South Carolina's Sea Islands, to teach literacy to allow blacks to pass voting tests. The program was an enormous success, tripling the number of black voters on St. John Island. The program was taken over by the SCLC and copied in Tennessee, Georgia, and Alabama.

Students organized sit-ins like the February 1960 protest at Woolworth's lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina. By the end of 1960 the sit-ins had spread to every southern and border state and even to Nevada, Illinois, and Ohio. Demonstrators focused not only on lunch counters but on parks, beaches, libraries, theaters, museums, and other public places. When they were arrested, student demonstrators made "jail-no-bail" pledges to call attention to their cause and to reverse the cost of protest (putting the financial burden of jail space and food on the jailors). Students organized sit-ins like the February 1960 protest at Woolworth's lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina. By the end of 1960 the sit-ins had spread to every southern and border state and even to Nevada, Illinois, and Ohio. Demonstrators focused not only on lunch counters but on parks, beaches, libraries, theaters, museums, and other public places. When they were arrested, student demonstrators made "jail-no-bail" pledges to call attention to their cause and to reverse the cost of protest (putting the financial burden of jail space and food on the jailors).

The 1961 Freedom Rides on public buses tested compliance with court orders to desegregate interstate transportation terminals. Nonviolent resistance became a particularly potent tool in the early days of the television era. Civil rights activists took advantage of emerging national network-news reporting, especially television, to capture national attention and the attention of Congress and the White House. The media was critical in exposing Southern realities to the nation at large, including many in the South who preferred to ignore them.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964, which required equal access to public places and outlawed discrimination in employment, was a major victory of the black freedom struggle, followed by the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The 1965 Act suspended literacy tests and other voter tests and authorized federal supervision of voter registration in states and individual voting districts where such tests were being used. African Americans who had been barred from registering to vote finally had an alternative to the courts. If voting discrimination occurred, the 1965 Act authorized the attorney general to send federal examiners to replace local registrars. The Civil Rights Act of 1964, which required equal access to public places and outlawed discrimination in employment, was a major victory of the black freedom struggle, followed by the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The 1965 Act suspended literacy tests and other voter tests and authorized federal supervision of voter registration in states and individual voting districts where such tests were being used. African Americans who had been barred from registering to vote finally had an alternative to the courts. If voting discrimination occurred, the 1965 Act authorized the attorney general to send federal examiners to replace local registrars.

The Act had an immediate impact. Within months of its passage on August 6, 1965, one quarter of a million new black voters had been registered, one third by federal examiners. Within four years, voter registration in the South had more than doubled. In 1965, Mississippi had the highest black voter turnout--74%--and led the nation in the number of black leaders elected. In 1969, Tennessee had a 92.1% turnout; Arkansas, 77.9%; and Texas, 73.1%.

Winning the right to vote changed the political landscape of the South. When Congress passed the Voting Rights Act, barely 100 African Americans held elective office in the U.S.; by 1989 there were more than 7,200, including more than 4,800 in the South. Nearly every Black Belt county in Alabama had a black sheriff, and southern blacks held top positions within city, county, and state governments. Atlanta boasted a black mayor, Andrew Young, as did Jackson, Mississippi--Harvey Johnson, and New Orleans, with Ernest Morial. Black politicians on the national level included Barbara Jordan, who represented Texas in Congress, and former mayor Young, who was appointed U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations during the Carter Administration. Julian Bond was elected to the Georgia Legislature in 1965, although political reaction to his public opposition to U.S. involvement in Vietnam prevented him from taking his seat until 1967. John Lewis currently represents Georgia's 5th Congressional District in the United States House of Representatives, where he has served since 1987. Lewis sits on the House Ways and Means and Health committees.

|