Long and Lean:

Cranes are large birds with long necks and legs, and some species are the tallest flying birds in the world! Their streamlined bodies, long, rounded wings, and grace in flight make them very easy to recognize. When flying, their bodies form straight lines from the tips of their bills to their toes.

Not Too Picky: Cranes are opportunistic feeders that may change their diet according to the season. They eat suitably sized prey such as small rodents, fish and amphibians, but will eat grain and berries during late summer and autumn Not Too Picky: Cranes are opportunistic feeders that may change their diet according to the season. They eat suitably sized prey such as small rodents, fish and amphibians, but will eat grain and berries during late summer and autumn

(the cranberry is so-named from its being extensively eaten by some northern species of crane).

They Stick Their Necks Out: Unlike the similar-looking but unrelated herons, cranes fly with necks outstretched, not pulled back.

Few and Far Between: While cranes travel to all the continents except Antarctica and South America, everywhere crane numbers are diminishing. The plight of the Whooping Cranes of North America inspired some of the first US legislation to protect endangered species.

Dance, Dance Revolution: Cranes young and old participate in elaborate "dances," to develop social skills, court mates, prepare to breed, and even have fun! Often, a whole flock of cranes will join in one a dance has started. These elaborate sequences of bows, leaps, runs, short flights, and noises are truly a sight to behold... And essential to crane reproduction.

Sibling Rivalry: Some cranes lay four eggs in a clutch, but most species lay only two. Cranes laying in warm climates produce white, or light-colored eggs to reflect excess heat. In colder climates, crane eggs tend to be dark to absorb heat. Sibling Rivalry: Some cranes lay four eggs in a clutch, but most species lay only two. Cranes laying in warm climates produce white, or light-colored eggs to reflect excess heat. In colder climates, crane eggs tend to be dark to absorb heat.

Though some species only raise one chick, others raise two. One chick will always grow to be the dominant sibling, and if food is scarce, the weaker sibling often starves.

Watch and Learn: Crane chicks are born rather strong, and their parents start feeding them right after they hatch. These chicks have brown or gray feathers that provide excellent camouflage. Chicks grow quickly and follow their parents to food sources to learn how to feed through observation.

'Adults lovingly tend to their chicks for several months. After two to four months,chicks develop flight feathers so they can keep up during their long migrations.

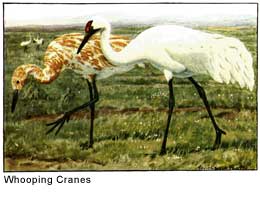

The Whooping Crane: The Whooping Crane (Grus americana) is a very large crane. It is the tallest North American bird and the only crane species found solely in North America. Whoopers are named for their distinctive calls.

Thin, White Dukes: Adults are white; they have a red crown and a long, dark, pointed bill. They have long dark legs which trail behind in flight and a long neck that is kept straight in flight. Black wing tips can be seen in flight. Immature birds are pale brown.

Nest and Nestlings: Their breeding habitat is muskeg; the only known nesting location is Wood Buffalo National Park in Canada and the surrounding area. Nest and Nestlings: Their breeding habitat is muskeg; the only known nesting location is Wood Buffalo National Park in Canada and the surrounding area.

They nest on the ground, usually on a raised area in a marsh. The female lays 1 to 3 eggs. Both parents feed the young. Usually no more than one young bird survives in a season.

Save the Cranes: Attempts have been made to establish other breeding populations in the wild.

Part I: One project involved cross-fostering with Sandhill Cranes. The Whooping Cranes failed to mate and reproduce; the project was suspended.

Part II: A second involved the establishment of a non-migratory population near Kissimmee, Florida. This population currently numbers about 58 birds; while problems with high mortality and lack of reproduction are addressed no further birds will be added to the population.

Part III: A third attempt has involved the reintroduction of the Whooping Crane to a new flyway established east of the Mississippi river. This project uses isolation rearing of young Whooping Cranes and trains them to follow ultra light aircraft. These birds are costume reared from hatching, taught to follow an ultra light aircraft, fledged over their future breeding territory in Wisconsin, and led by ultra light on their first migration from Wisconsin to Florida; the birds learn the migratory route and then return, on their own, the following spring.

This reintroduction began in fall, 2001 and has added birds to the population in each subsequent year. As of April, 2006 there are 64 surviving Whooping Cranes in the Eastern Migratory Population (EMP), including 19 yearlings lead by ultra light aircraft in fall, 2005 and 4 yearlings released in Wisconsin and allowed to migrate on their own (Direct Autumn Release (DAR)). Fourteen of these birds have formed seven pairs; two of the pairs nested and produced eggs in spring, 2005. The eggs were lost due to parental inexperience.

Success At Last! Thus far in spring, 2006 some of the same pairs have again nested and are incubating eggs. Two whooping crane chicks were hatched on June 22, 2006. Their parents are both birds that were hatched and led by ultra light on their first migration in 2002. At just 4 years old these are young parents. The chicks are the first whooping cranes hatched in the wild, of migrating parents, east of the Mississippi, in over 100 years.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Brolga: In 1926 the Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union made Brolga, a popular name derived from Gamilaraay burralga, the official name of the bird. It is sometimes referred to as the The Brolga: In 1926 the Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union made Brolga, a popular name derived from Gamilaraay burralga, the official name of the bird. It is sometimes referred to as the

"Native Companion". The Brolga is a common wetland congregating bird species in tropical and eastern Australia, well known for its intricate mating dance.

Weights and Measures: The full-grown Brolga is a tall, mid-grey to silver-grey crane, 0.7 to 1.3 m high, with a wingspan of 1.7 to 2.4 m, and a broad red band extending from the straight, bone-colored bill around the back of the head. Juveniles lack the red band. Adult males weigh a little under 7 kg, females a little under 6 kg.

Coo Coo for Tubers: Brolga are omnivorous and eat a variety of wetland plants, insects, invertebrates, and small vertebrates such

as frogs. They also eat wetland and upland plants, seeds, mollusks, and crustaceans. Northern Australian populations of Brolga are fond of the tubers of the bulkuru sedge which they dig holes to extract but this is not available south of Brisbane.

Range and Population: Brolgas are widespread and often abundant in north and north-east Australia, especially north-east Queensland, and are common as far south as Victoria. They are also found in southern New Guinea and as rare vagrants in New Zealand and the northern part of Western Australia. The population is estimated at between 20,000 and 100,000 and is not considered to be threatened. The International Crane Foundation began a captive breeding population with three pairs of wild Brolga which were captured in 1972. Brolga are non-migratory but do move in response to seasonal rains.

Family and Flock: There are many Brolgas on the endless Australian plains today. Brolgas are gregarious creatures; the basic social unit is a pair or small family group of about 3 or 4 birds, usually parents together with juvenile offspring, though some such groups are nonfamilial. In the non-breeding season, they gather into large flocks, which appear to be many self-contained individual groups rather than a single social unit. Within the flock, families tend to remain separate and to coordinate their activities with one another rather than with the flock as a whole. Family and Flock: There are many Brolgas on the endless Australian plains today. Brolgas are gregarious creatures; the basic social unit is a pair or small family group of about 3 or 4 birds, usually parents together with juvenile offspring, though some such groups are nonfamilial. In the non-breeding season, they gather into large flocks, which appear to be many self-contained individual groups rather than a single social unit. Within the flock, families tend to remain separate and to coordinate their activities with one another rather than with the flock as a whole.

Tango, Tango, Tango: Brolgas are well known for their intricate mating dances. The dance begins with a bird picking up some grass and tossing it into the air, catching it in its bill, then progresses to jumping a meter into the air with outstretched wings, then stretching, bowing, walking, calling, and bobbing its head. Sometimes just one Brolga dances for its mate; often they dance in pairs; and sometimes a whole group of about a dozen dance together, lining up roughly opposite each other before starting.

Nest and Nestlings: In the breeding season, which is largely determined by rainfall rather than the time of year, the flocks split up and pairs establish nesting territories in wetlands. In good habitat, nests can be quite close together, and are often found in the same area as those of the closely related but slightly larger Sarus Crane. The nest is a raised mound, built by both sexes, of sticks, uprooted grass, and other plant material sited on a small island, standing in shallow water, or occasionally floating. If no grasses are available, mud or roots unearthed from marsh beds are employed. Sometimes they make barely any nest at all, take over a disused swan nest, or simply lay on bare ground.

A pair of spotted or blotched white eggs are most common, but sometimes the clutch is one or three, laid about two days apart. Both birds incubate and guard the young. Hatching is not synchronized, and takes about 30 days. The chicks hatch covered in grey down and weighing about 100 g. They can leave the nest within a day or two, have body feathers within 4 or 5 weeks, and are fully feathered after three months, and able to fly about two weeks after that. When threatened, chicks hide and stay quiet while the parents perform a broken-wing display. The parents continue to guard the young for up to 11 months, or almost two years if they do not re-nest.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Demoiselle Crane: The Demoiselle Crane, Anthropoides virgo is a species of crane. It breeds in central Asia, with a few found in Cyprus and eastern Turkey, and migrates to Africa in winter.

Weights and Measures: The Demoiselle is 85-100 cm long with a 155-180 cm wingspan. It is therefore slightly smaller than the Common Crane, with similar plumage. However it has a long white neck stripe and the black on the fore neck extends down over the chest in a plume. Weights and Measures: The Demoiselle is 85-100 cm long with a 155-180 cm wingspan. It is therefore slightly smaller than the Common Crane, with similar plumage. However it has a long white neck stripe and the black on the fore neck extends down over the chest in a plume.

It has a loud trumpeting call, higher-pitched than the Common Crane. Like other cranes it has a dancing display, more balletic than the Common Crane, with less leaping.

Home, Sweet Home: During the breeding season, marshy areas are preferred living spaces, while the cranes are more commonly found in dry grasslands throughout the winter. The birds usually nest no more than 500 m away from a main source of water. Damp marshes, steppe habitats, and meadows are all other areas in which the Demoiselle Crane could be spotted in. The range in height goes from sea level to over 10,000 meters.

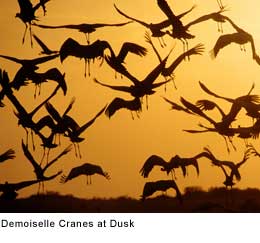

Migration of All Migrations: Demoiselle cranes have to take one of the toughest migrations in the world. In late August through September, they gather in flocks of up to 400 individuals and prepare for their flight to their winter range. During their migratory  flight south, demoiselles fly like all cranes, with their head and neck straight forward and their feet and legs straight behind, reaching altitudes of 16,000-26,000 feet (4,875-7,925 m). flight south, demoiselles fly like all cranes, with their head and neck straight forward and their feet and legs straight behind, reaching altitudes of 16,000-26,000 feet (4,875-7,925 m).

Along their arduous journey they have to cross the Himalayan mountains to get to their over wintering grounds in India, many die from fatigue, hunger and predation from birds such as eagles.

At their wintering grounds, demoiselles have been observed flocking with Eurasian cranes, their combined totals reaching up to 20,000 individuals. Demoiselles maintain separate social groups within the larger flock. In March and April, demoiselle cranes begin their long spring journey back to their northern nesting grounds.

Status in the Wild: The Demoiselle Crane is evaluated as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. It is one of the species to which the Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (AEWA) applies.

Few and Far Between: There are representatives of this group on all the continents except Antarctica and South America. Everywhere crane numbers are diminishing. The plight of the Whooping Cranes of North America inspired some of the first US legislation to protect endangered species.

Myth and Lore:

Beautiful Dancers: The cranes' beauty and their spectacular mating dances have made them highly symbolic birds from earliest times. Crane myth is as widely separated and universal as the Aegean, South Arabia, Japan and Amerindian North America. In northern Hokkaido, the women of the Ainu people, whose culture is more Siberian than Japanese,  performed a crane dance that was captured in 1908 in a photograph by Arnold Genthe. In Korea, a crane dance has been performed in the courtyard of the Tongdosa Temple since the Silla Dynasty (646 CE). performed a crane dance that was captured in 1908 in a photograph by Arnold Genthe. In Korea, a crane dance has been performed in the courtyard of the Tongdosa Temple since the Silla Dynasty (646 CE).

In Mecca, in pre-Islamic South Arabia, the goddesses Allat, Uzza, and Manah, who were believed to be daughters of and intercessors with Allah, were called the "three exalted cranes" (gharaniq, an obscure word on which 'crane' is the usual gloss). See The Satanic Verses for the best-known story regarding these three goddesses.

The Greek for crane is Γερανος (Geranos), which gives us the Cranesbill, or hardy geranium. The crane was a bird of omen. In the tale of Ibycus and the cranes, a thief attacked Ibycus (a poet of the 6th century BCE) and left him for dead. Ibycus called to a flock of passing cranes, who followed the murderer to a theater and hovered over him until, stricken with guilt, he confessed to the crime.

Pliny the Elder wrote that cranes would appoint one of their number to stand guard while they slept. The sentry would hold a stone in its claw, so that if it fell asleep it would drop the stone and waken.

Aristotle describes the migration of cranes in The History of Animals, adding an account of their fights with Pygmies as they wintered near the source of the Nile. He describes as untruthful an account that the crane carries a touchstone inside it that can be used to test for gold when vomited up. (This second story is not altogether implausible, as cranes might ingest appropriate gizzard stones in one locality and regurgitate them in a region where such stone is otherwise scarce)

The Egyptian hieroglyphic symbol for the letter "B" is the crane.

France: Also, the word "pedigree" comes from the Old French phrase, "pie de grue", which means "foot of a crane", as the pedigree diagram looks similar to the branches coming out of a crane's foot.

Japan: A crane is considered auspicious in Japan, as one of the symbols of longevity and represented with other symbols of long life, the pine and bamboo, and the tortoise. In feudal Japan the crane was protected

by the ruling classes and fed by the peasants. Japan: A crane is considered auspicious in Japan, as one of the symbols of longevity and represented with other symbols of long life, the pine and bamboo, and the tortoise. In feudal Japan the crane was protected

by the ruling classes and fed by the peasants.

When the feudal system was abolished in the Meiji era of the 19th century, the protection of cranes was lost. With effort they have been brought back from the

brink of extinction. Japan has named one of their satellites tsuru (crane, the bird). If one folds 1000 origami cranes, according to tradition, one's wish for health will be granted. Since the death of Sadako Sasaki this applies to a wish for peace as well.

China: For traditional Chinese 'heavenly cranes' (tian-he) or 'blessed cranes' (xian-he) were messengers of wisdom. Legendary Taoist sages were transported between heavenly worlds on the backs of cranes.

All text is available under the terms

of the GNU Free Documentation License

|