|

Just the Facts: The albatrosses are a group of large to very large birds; they are the largest of the procellariiformes. Their bills are large, strong and sharp-edged, the

upper mandibles terminating in large hooks. These bills are composed of several horny plates, and along the sides are the two "tubes," long nostrils that give the order

its name.

Beak or Nose? The tubes of all albatrosses are along the sides of the bill, unlike the rest of the Procellariiformes where the tubes run along the top of Beak or Nose? The tubes of all albatrosses are along the sides of the bill, unlike the rest of the Procellariiformes where the tubes run along the top of

the bill. These tubes allow the albatros-

ses to have an acute sense of smell,

an unusual ability for birds. Like other Procellariiformes they use this olfactory ability while foraging in order to locate potential food sources.

They Walk the Walk: The feet have no hind toe and the three anterior toes

are completely webbed. The legs are strong for Procellariiformes, in fact, almost uniquely amongst the order in that they and the giant petrels are able to walk well

on land.

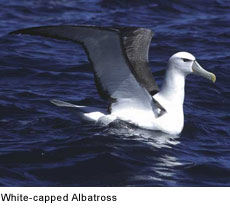

Tasteful Plumage: The adult plumage of most of the albatrosses is usually some variation of dark upper-wing and back, white undersides, often compared to that of a gull. Of these, the species range from the Southern Royal Albatross which is almost completely white except for the ends of the wings, to the Amsterdam Albatross which has an almost juvenile-like breeding plumage with a great deal of brown, particularly a strong brown band around the chest. Tasteful Plumage: The adult plumage of most of the albatrosses is usually some variation of dark upper-wing and back, white undersides, often compared to that of a gull. Of these, the species range from the Southern Royal Albatross which is almost completely white except for the ends of the wings, to the Amsterdam Albatross which has an almost juvenile-like breeding plumage with a great deal of brown, particularly a strong brown band around the chest.

Spanning Wings: The wingspans of the largest great albatrosses (genus Diomedea) are the largest of any bird, exceeding 340 cm (over 11 feet), although the other species' wingspans are considerably smaller. The wings are stiff and cambered, with thickened streamlined leading edges.

Where the Albatross Roam: Most albatrosses range in the southern hemisphere from Antarctica to Australia, South Africa and South America. The need for wind in order to glide is the reason albatrosses are for the most part confined to higher latitudes; being unsuited to sustained flapping flight makes crossing the doldrums extremely difficult. The exception, the Waved Albatross, is able to live in the equatorial waters around the Galapagos Islands because of the cool waters of the Humboldt Current and the resulting winds.

Dynamic Soaring: Albatrosses travel huge distances with two techniques used by many long-winged seabirds, dynamic soaring and slope soaring. Dynamic soaring enables them to minimize the effort needed by gliding across wave fronts gaining energy from the vertical wind gradient. Slope soaring is more straightforward: the albatross turns to the wind, gaining height, from where it can then glide back down to the sea.

They Float Through the Air With the Greatest of Ease: Albatross have high glide ratios, around 1:22 to 1:23, meaning that for every meter they drop, they can travel forward 22 meters. They are aided in soaring by a shoulder-lock, a sheet of tendon that locks the wing when fully extended, allowing the wing to be kept up and out without any muscle expenditure, a morphological adaptation they share with the giant petrels. They Float Through the Air With the Greatest of Ease: Albatross have high glide ratios, around 1:22 to 1:23, meaning that for every meter they drop, they can travel forward 22 meters. They are aided in soaring by a shoulder-lock, a sheet of tendon that locks the wing when fully extended, allowing the wing to be kept up and out without any muscle expenditure, a morphological adaptation they share with the giant petrels.

Sailors in the Sky: Albatrosses combine these soaring techniques with the use of predictable weather systems; albatrosses in the southern hemisphere flying north from their colonies will take a clockwise route, and those flying south will fly counterclockwise.

Relaxing in the Clouds: Albatrosses are so well adapted to this lifestyle that their heart rates while flying are close to their basal heart rate when resting. This efficiency is such that the most energetically demanding aspect of a foraging trip is not the distance covered, but the landings, take-offs and hunting they undertake having found a food source.

Who Needs Flapping? This efficient long-distance traveling underlies the albatross's success as a long-distance forager, covering great distances and expending little energy looking for patchily distributed food sources. Their adaptation to gliding flight makes them dependent on wind and waves, however, as their long wings are ill-suited to powered flight and most species lack the muscles and energy to undertake sustained flapping flight.

Wind Beneath Their Wings: Albatrosses in calm seas are forced to rest on the ocean's surface until the wind picks up again. They also sleep while resting on the surface (and not while on the wing as is sometimes thought). The North Pacific albatrosses can use a flight style known as flap-gliding, where the bird progresses by bursts of flapping followed by gliding. When taking off, albatrosses need to take a run up to allow enough air to move under the wing to provide lift.

Albatross Appetites: Albatrosses feed on squid, fish and krill by either scavenging, surface seizing or diving.

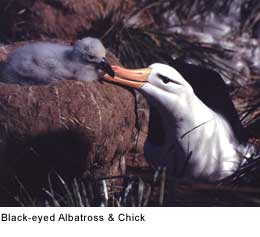

Nest and Nestlings: Albatrosses are colonial, nesting for the

most part on remote oceanic Nest and Nestlings: Albatrosses are colonial, nesting for the

most part on remote oceanic

islands, often with several species nesting together.

Pair bonds between males and females form over several years, with the use of ritualized dances, and will last for the life of the pair.

A breeding season can take over a year from laying to fledging,

with a single egg laid in each

breeding attempt.

Albatross in Danger: Of the 21 species of albatrosses recognized by the IUCN, 19 are threatened with extinction.

Numbers of albatrosses have declined in the past due to harvesting for feathers, but today the albatrosses are threatened by introduced species such as rats and feral cats that attack eggs, chicks and nesting adults; by pollution; by a serious decline in fish stocks in many regions largely due to over fishing; and by long-line fishing. Numbers of albatrosses have declined in the past due to harvesting for feathers, but today the albatrosses are threatened by introduced species such as rats and feral cats that attack eggs, chicks and nesting adults; by pollution; by a serious decline in fish stocks in many regions largely due to over fishing; and by long-line fishing.

Long-line fisheries pose the greatest threat, as feeding birds are attracted to the bait and become hooked on the lines and drown. Governments, conservation organizations and fishermen are all working towards reducing this by-catch.

What's in a Name? The name albatross is derived from the Arabic al-câdous or al-g.at,t,a-s (a pelican; literally, "the diver"), which traveled to English via the Portuguese form alcatraz ("gannet"). The OED notes that the word alcatraz was originally applied to the frigatebird; the modification to albatross was perhaps influenced by Latin albus, meaning "white", in contrast to frigatebirds which are black. The Portuguese word albatroz is of English origin.

The Goonies: They were once commonly known as Goonie birds or Gooney birds, particularly those of the North Pacific. In the southern hemisphere, the name mollymawk is still well established in some areas, which is a corrupted form of malle-mugge, an old Dutch name for the Northern Fulmar. The name Diomedea, assigned to the albatrosses by Linnaeus, references the mythical metamorphosis of the companions of the Greek warrior Diomedes into birds.

Legendary Birds: Albatrosses have been described as "the most legendary of all birds". An albatross is a central emblem in The Rime of the Ancient Mariner by Samuel Taylor Coleridge; a captive albatross is also a metaphor for the poète maudit in a poem of Charles Baudelaire. It is from the former poem that the usage of albatross as a metaphor is derived; someone with a burden or obstacle is said to have 'an albatross around their neck', the punishment given in the poem to the mariner who killed the albatross. Legendary Birds: Albatrosses have been described as "the most legendary of all birds". An albatross is a central emblem in The Rime of the Ancient Mariner by Samuel Taylor Coleridge; a captive albatross is also a metaphor for the poète maudit in a poem of Charles Baudelaire. It is from the former poem that the usage of albatross as a metaphor is derived; someone with a burden or obstacle is said to have 'an albatross around their neck', the punishment given in the poem to the mariner who killed the albatross.

In part due to the poem, there is a widespread myth that sailors believe it disastrous to shoot or harm an albatross; in truth, however, sailors regularly killed and ate them, but they were often regarded as the souls of lost sailors. More recently, they have become part of popular culture, for example, in a Monty Python sketch, or the song "Echoes" by Pink Floyd. In the movie Serenity, the character River was referred to

as an albatross by The Operative, reflecting the widespread adoption of the word

as a metaphor.

Albatross Watching: Albatrosses are popular birds for bird watchers and their colonies popular destinations for ecotourists. Regular bird watching trips are taken out of many costal towns and cities, like Monterey, Kaikoura, Wollongong and Sydney, to see pelagic seabirds, and albatrosses are easily attracted to these sightseeing boats by the deployment of fish oil into the sea. Visits to colonies can be very popular; the Northern Royal Albatross colony at Taiaroa Head in New Zealand attracts 40,000 visitors a year, and more isolated colonies are regular attractions on cruises to sub-Antarctic islands.

How Many? The albatrosses comprise between 13 and 24 species (the number of species is still a matter of some debate, 21 being the most commonly accepted number) in 4 genera. The four genera are the great albatrosses (Diomedea), the mollymawks (Thalassarche), the North Pacific albatrosses  (Phoebastria), and the sooty albatrosses or sooties (Phoebetria). Of the four genera, the North Pacific albatrosses are considered to be a sister taxon to the great albatrosses, while the sooty albatrosses are considered closer to the mollymawks. (Phoebastria), and the sooty albatrosses or sooties (Phoebetria). Of the four genera, the North Pacific albatrosses are considered to be a sister taxon to the great albatrosses, while the sooty albatrosses are considered closer to the mollymawks.

Classification Confusion: The taxonomy of the albatross group has been a source of a great deal of debate. The Sibley-Ahlquist taxonomy places seabirds, birds of prey and many others in a greatly enlarged order Ciconiiformes, whereas the ornithological organizations in North America, Europe, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand retain the more traditional order Procellariiformes. The albatrosses can be separated from the other Procellariiformes both genetically and through morphological characteristics, size, their legs and the arrangement of their nasal tubes (see Morphology and flight).

Within the family the assignment of genera has been debated for over a hundred years. Originally placed into a single genus, Diomedea, they were rearranged by Reichenbach into four different genera in 1852, then lumped back together and split apart again several times, acquiring 12 different genus names in total (though never more than eight at one time) by 1965 (Diomedea, Phoebastria, Thalassarche, Phoebetria, Thalassageron, Diomedella, Nealbutrus, Rhothonia, Julietata, Galapagornis, Laysanornis, and Penthirenia).

Recent research by Gary Nunn of the American Museum of Natural History (1996) and other researchers around the world studied the mitochondrial DNA of all 14 accepted species, finding that there were four monophyletic groups within the albatrosses. They proposed the resurrection of two of the old genus names, Phoebastria for the North Pacific albatrosses and Thalassarche for the mollymawks, with the great albatrosses retaining Diomedea and the sooty albatrosses staying in Phoebetria. Both the British Ornithologists' Union and the South African authorities split the albatrosses into four genera as Nunn suggested, and the change has been accepted by the majority of researchers.

All text is available under the terms

of the GNU Free Documentation License

|